If you’ve ever visited the Nichols House Museum, you will already know that Rose Standish Nichols was an avid tea drinker. This is not only reflected in the museum’s physical collection but in its history. For years, Rose hosted salon-style tea parties, attended by a carefully cultivated group of influential society members with a connection to the host herself or the topic of the day. For our December blog post, we will examine the relationship between tea and our matriarch, Rose.

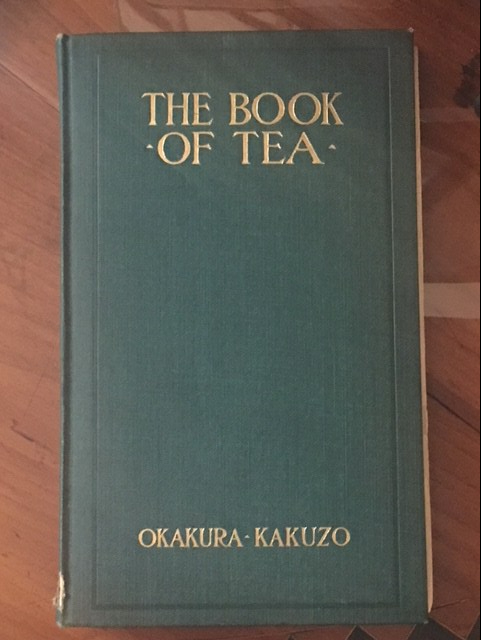

The Book of Tea by Okakura Kakuzo was published in 1906. Kakuzo was an influential art critic who eventually became curator of the Oriental art department at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Born in Yokohama in 1863, he attended Tokyo Imperial University, where he met a fellow art critic who strove to defend traditional Japanese art against westernization. Kakuzo became an outspoken defender of the traditional Japanese art forms, co-founding and later becoming head of Tokyo Fine Arts School. He later founded the Japan Academy of Fine Arts. It was toward the turn of the century that he came to the Boston MFA, where he continued to assert the importance of traditional Oriental art. His books, including The Book of Tea, were published in English so that even Westerners would be able to understand his ideas and opinions on Oriental art. Kakuzo died in Japan in 1913. [1]

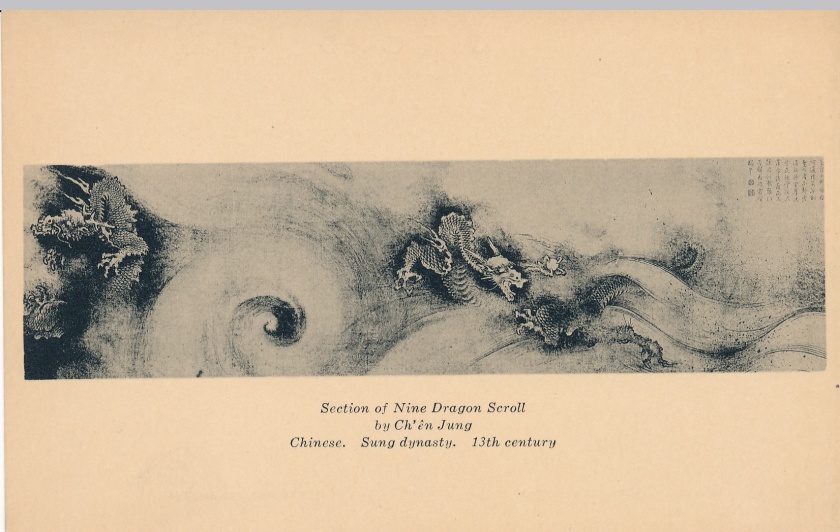

In Kakuzo’s book he mentions tea in connection with three major Chinese dynasties: Tang (618-906), Sung (960-1279), and Ming (1368-1644). Tea became the “undisputed national drink of China” under the Tang Dynasty; began to be “powdered and whisked” under the Sung Dynasty; and began to be sipped from porcelain instead of wooden bowls under the Ming Dynasty [2].Rose Nichols’ extensive postcard collection features several images attributed to these dynasties.

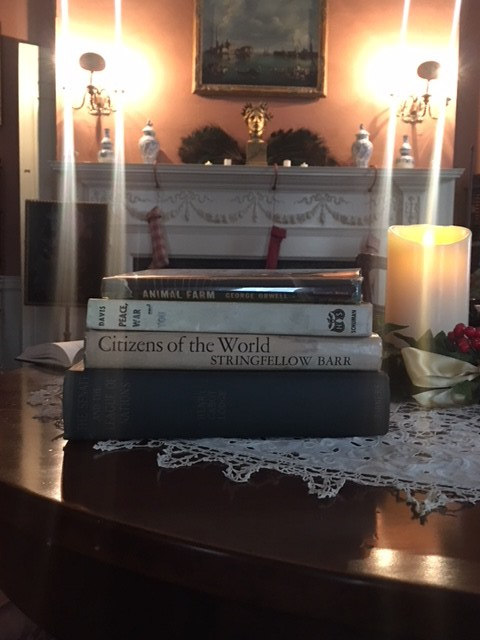

In addition to The Book of Tea, Rose also collected many books that could have easily been featured in her reading club. Her salon-style discussion were known to push the boundaries of what some might consider traditional tea-time talk. As Rose was keen on world peace, many of the books she collected reflect her interests in global affairs. It’s quite possible she used these books to draw attention to events and governments her guests were unaware of. An extensive traveler, Rose collected such broad topics as covered in books like the ones you see below, including George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1946) and Olive Schreiner’s Woman and Labor (1911).

The relationship between Rose Standish Nichols and tea has continued to influence the museum. Our interpretation of this independent, accomplished woman’s house would be incomplete without calling attention to how and why Rose hosted lively discussions over tea in the parlor of her home for decades. If you have yet to visit the museum, come by before February 3rd, 2018 to see our pop-up exhibit, Peace and Prosperity: Rose Standish Nichols and Tea, which includes special items that showcase the relationship we’ve examined here today.

Notes

[1] Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Okakura Kakuzo.” 16 March, 2016. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

[2] Moxham, Roy. Tea: Addiction, Exploitation, and Empire. Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003.

By Victoria Johnson, Visitor Services and Research Associate

You must be logged in to post a comment.