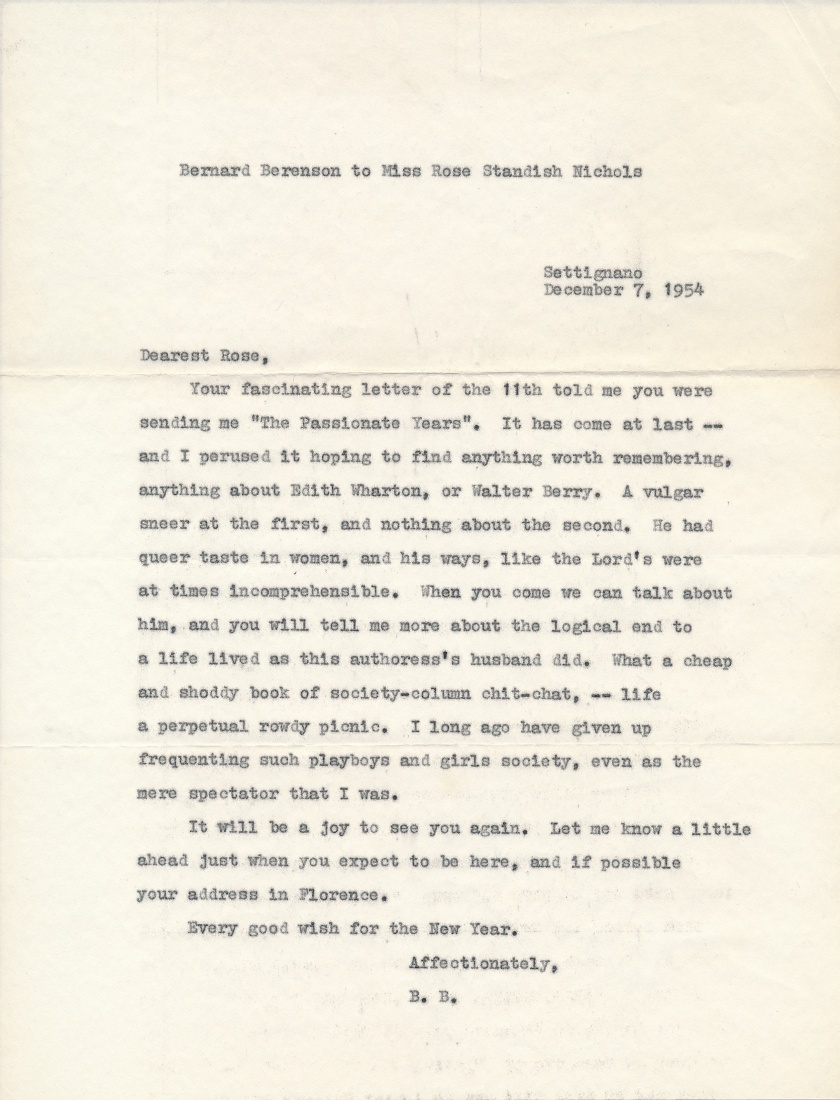

Bernard Berenson (1865-1959) was an art critic and historian whom some believe was the definitive art historian in America during the 20th century. Born in Lithuania, Berenson and his family moved to Boston in 1875. Bernard, or BB, as he was later called, attended many of this city’s most enduring schools: Boston Latin School, Boston University, and Harvard University. Upon his graduation, patrons such as Isabella Stewart Gardner supported his definitive Grand Tour of Europe. Berenson continued to travel throughout his life, learning and observing art on an international scale. Eventually, patrons solicited his opinion on Renaissance art in particular–his area of expertise. Today, Berenson is considered (by some) a controversial figure for his secret partnership with Joseph Duveen (1869-1939), an international art dealer. Upon his death, Berenson bequeathed his estate and works to Harvard University. (1)

Less renowned for her art collecting than her impressive activism, landscape architect and fellow world traveler Rose Standish Nichols became friends with the legendary art connoisseur. The two Bostonians shared an admiration for the Italian Renaissance in particular.

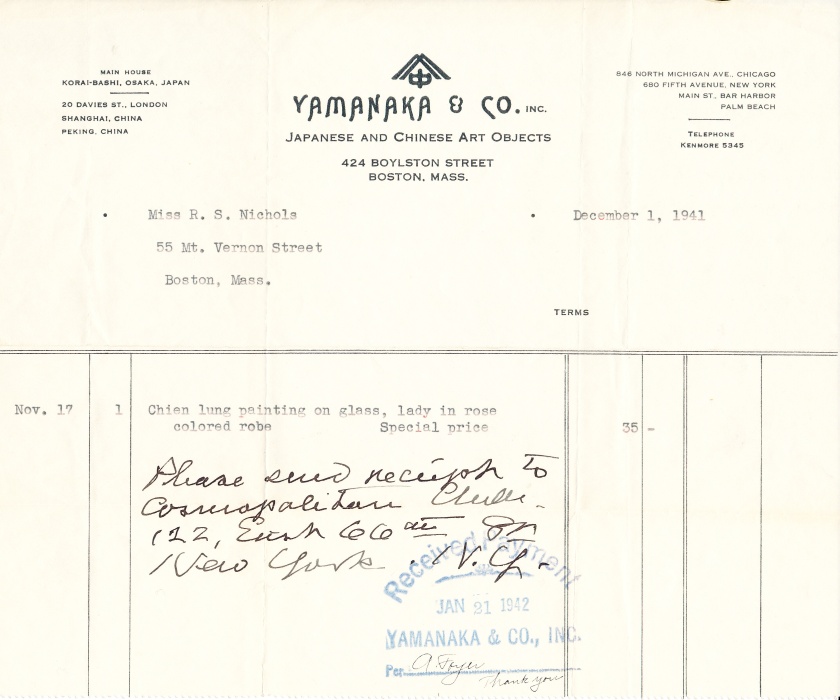

As a friend and an admirer of his work, Rose’s library at the Nichols House Museum contains no less than four books by the art historian: Lorenzo Lotto; An Essay in Constructive Art Criticism, The Venetian Painters of the Renaissance (1894), The Venetian Painters of the Renaissance (1897), and Echi E Riflessioni (Diario 1941-1944); the last of which Berenson personally inscribed to Rose.

Another friend of Rose’s provides us with a particularly humorous glimpse into Rose and Bernard’s friendship. In 1995, Polly Thayer Starr–whose portrait of Rose, you might recall, hangs in the Nichols House Museum library–gave an interview to Robert Brown for the Archives of American Art. Starr was the daughter of Rose’s friend Ethel Thayer. In 1927, Rose reluctantly agreed to sit as Starr’s subject, which she writes about here. With no shortage of anecdotes about Miss Rose Standish Nichols, Starr tells Brown one story about our matriarch which has become a favorite among the museum’s staff:

“There was one other story of Miss Nichols, that interested me because she had the Crown Princess of Greece come and stay with me. She was great friends with Bernard Berenson, the critic and writer, and one day she took a carriage out from Florence to see him, and the servant came to the door. She said she wanted to see Bernard Berenson, and the servant said she was very sorry, but Berenson was indisposed and couldn’t get up–wasn’t feeling well. “Well,” she said, “tell him I have three queens that have come to see him,” and wrote it on her card. The servant, quite impressed, took it up to Berenson, who looked out the window, and there he saw Queen Sophie of Greece, the Queen of Italy–Margarita, I believe her name was–and the Queen of Yugoslavia. So he said he’d be right down. [laughter] But she knew all the politicians, crowned heads and prime ministers that she could contact, and they were all amused by her. So when I went to Spain I went with her, and it was great fun.” (2)

*A note about the queens: if the Queen of Italy Thayer is referring to is Queen Margarita (reigned 1878-1900), she would likely not have been Queen at the time of this story. The above photograph, part of the Nichols Family Photograph Collection, shows Queen [H]elena, daughter-in-law of Queen Margarita, wife of Victor Emmanuel III, with whom she reigned from 1900 and 1946. Queen Sophia of Greece served from 1913 to 1917, then again from 1920 to 1922. Queen Maria of Yugoslavia reigned from 1922 and 1934. The photograph of Queen Olga Constantinovna of Russia shows that Rose was fascinated by many queens!

(1) . “Berenson, Bernard.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 18 Jul. 2017.

(2) Oral history interview with Polly Thayer, 1995 May 12-1996 February 1. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

![IMG_6385 Bernard's inscription to Rose: "To Rose Nichols / With the best remembrances of friendship of / Bernard Berenson / [illegible]/ March 1950"](https://i0.wp.com/nicholshousemuseum.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/img_6385.jpg?w=416&h=555&ssl=1)

![IMG_0002 Queen [H]elena of Italy*, Nichols Family Photograph Collection.](https://i0.wp.com/nicholshousemuseum.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/img_0002.jpg?w=417&h=639&ssl=1)

You must be logged in to post a comment.