By Elizabeth T. Weisblatt, Nichols House Museum Collections Intern

Visitors to the Nichols House Museum may be surprised to learn that it is home to a sizable collection of textiles, much of which is housed in permanent storage. As someone with a background in textile and fashion history, I was delighted to get the chance to survey the textiles as part of an inventory project I was assigned as the Nichols House Museum Collections Intern. In doing so, I discovered two nineteenth-century paisley shawls, 1961.804 and 1961.805 which I decided to research for the purposes of this blog.

Women’s fashion has for hundreds of years varied in more obvious ways than men’s fashion, overall. Silhouette changes and focal points (bust, shoulders, etc…) varied over time and how women accessorized often went hand in hand with whatever style was popular. However, there is one accessory that has endured since it debuted in Western fashion–even to today–although it has changed to suit modern needs. Paisley shawls, which were made as imitations of Kashmir shawls, were made popular by expanding trade routes into India. Cashmere wool comes from a goat living only in India and is the secondary fiber of specific goats to the region. One cashmere goat produces three to six ounces of fiber, depending upon the design and size, Kashmiri shawls from this period have been known to take up to eighteen months to three years [1]. Kashmiri shawls were known to have been made popular by Emperor Akbar as part of the royal court attire; they were also used as gifts…and sometimes bribes. There is an account of an English ambassador to the Mughal court in 1616 recorded having indignantly rejected one such offer [2].

First made popular at the end of the eighteenth century, these pieces were not just a sign of luxury, but a way to stay warm while still showing off a form-fitting dress. Empress Joséphine, first wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, while not originally enthusiastic about these pieces, warmed up to them quickly (pun intended), and is purported to have had them brought to the French court by the trunk load. Not only did they make fashionable accessories, but their size also allowed them to be made into dresses and capes [3]. For example, 1961.804 is 54.5 inches wide and 121.5 inches long.

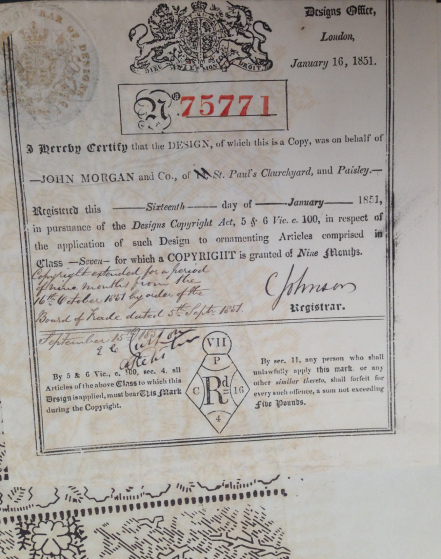

Paisley shawls, as they are known today, got their name from the industry boom created in the town of Paisley, Scotland. While created in America, France, and throughout the UK, Paisley gained a reputation for finely crafted works of art with designers that were willing to delve into very complex designs. When production first began, designers took inspiration from Indian designs and France became known for high-quality imitations [3]. However, as Copyright law of the time had yet to catch up to the rate of production, and designs could only be registered for months at a time, designs were easily traded and copied across city and country borders.

Eventually, because of the subdivision of labor combined with the cheaper cost of living, the town of Paisley became the epicenter in the UK and the town’s name is now synonymous with the design [4]. The town of Paisley became an epicenter for these pieces, in large part because the town had a previous history of textile manufacture, however, France was first in large scale Kashmiri shawl imitation production.

While Paisley shawls may not have been as soft as true cashmere shawls, the use of wool combined with silk or cotton created a much softer texture than pure European wool. These pieces were warm, fashionable, and available at different price points.

In the early 1790s, both Edinburgh, Scotland and Norwich, England began to imitate Kashmir shawls on hand looms; Paisley followed in 1805. Paisley introduced an attachment to the handloom in 1812, which enabled five different colors of yarn to be used, instead of just two colors, indigo and madder, thus better imitating the Kashmir shawls. Agents were sent from Paisley to London to copy the latest Kashmir shawls as they arrived by sea and, in eight days imitations were being sold in London for £12, the original Kashmir shawl costing £70-100. Paisley shawls offered fashionable accessories to middle and lower class women on a scale unheard of previously [5].

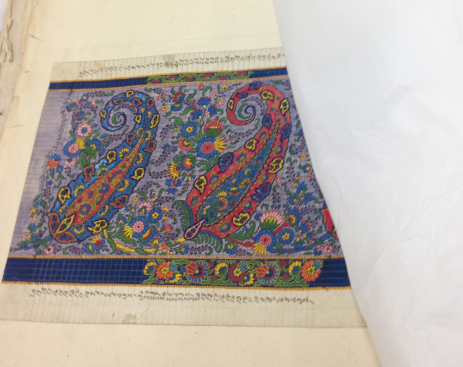

Multiple pieces in the collection show the evolution in the design and use of paisley shawls, as seen in the Nichols House Museum example, pictured below, 1961.804. This early nineteenth-century shawl was made using a blend of high-quality wool and silk fibers are woven using a twill weave. Similar to the design on Empress Joséphine’s dress, the addition of an encasing border denotes the piece as being European in design as freestanding or floating designs were not to the overall tastes of Europeans [6].

The rich red of the shawl still gives the piece what would have been considered an exotic feel, and the flowers that make up the larger paisleys are stylized in a European manner, which would be recognizable and more desirable to the Western market. While a bold use of color, the piece is of a simpler creation, as the loom that created it would be the width of the shawl and use one color throughout, with no alternating or hidden colors, called floats. It is these floats along with the style of the design that can help to date the piece; at the time looms in Europe could only handle the use of five colors. If these colors were only meant to be seen in specific areas, the lengths would be hidden on the underside of the shawl, which also created an inverse of the design on the front. The softness and quality of the shawl, combined with the design motif, lends itself to be a piece most likely manufactured in France, within 1820-1830.

Advancement in loom technology allowed the use of additional, sometimes hidden, threads in the weft (horizontal fibers) which eventually gave way to reversible shawls. Accented borders did not have to be separate pieces, or used solely for decoration.

As popularity grew, so did the need to market pieces to European and American tastes. While India continued to produce Kashmir shawls, the ongoing Industrial Revolution allowed Europe and America to create their own shawls as well, beginning with the invention of the Jacquard Loom in 1801. As weaving technology expanded, so too did the design potential.

1961.805, the second shawl, while coarser to the touch, is a perfect example of technological advancement as well as the expanding market. The patterns in both pieces use the same colors throughout, alternating dominant colors in the pattern.

The use of the Jacquard Loom takes a skilled worker to translate the design into a hole punch card – each hole selects the threads for the pattern and allows the hooks to pass through. The cards would then be stitched together in a chain to be fed into the loom, and the weaver creates the pattern by passing threads over and under one another using a shuttle to pass threads back and forth between the vertical threads (warp) to weave the longitudinal threads (weft).

The innovation of hole punch cards allowed workers to manipulate the pattern without the need of an on-hand assistant, or draw boy. The pattern in 1961.805 makes use of the ability to easily switch dominant colors, choosing red, black, yellow, purple, white and light green evenly throughout. While at first glance it is easy to describe the pattern as patterned stripes, a closer look allows us to see the alternating patterns.

Using the same pattern in alternating colors allows variance, without having to limit the color potential. It is pieced with similar all over patterns such as this that are sometimes seen in museum collections and antique stores as an entire coat, as these shawls were luxury heirloom pieces.

Paisley shawls became unfashionable during the 1870s for a combination of reasons, as the popularity of the bustle grew and prevented shawls from draping fashionably, as well as the decrease in price and increase in availability [3]. However, while purchasing new shawls was no longer fashionable, shawls were still usable fashion pieces, although their forms changed.

As previously mentioned, these sizable accessories could be made into dresses (as Empress Josephine was shown to do when first popularized), smoking jackets, or tea gowns. However, the utility and value did not stop at wearable pieces. If a shawl was still in overall good shape, using it as an accent over the couch or as a piano or table accent were common. Minor mending could be done to hide a hole or small tear, and an item strategically placed on top or simply folding the shawl would hide the damage.

Finding shawls with repairs in the same area, usually circular (from a vase) or square (box or keepsake) were common. If the shawl, however, was too damaged, perhaps passed between family members, cutting and using parts still in good shape was common as well. Pillows, doll’s dresses, curtains, or simply scrap for other shawls would make use of a prized and well-loved piece.

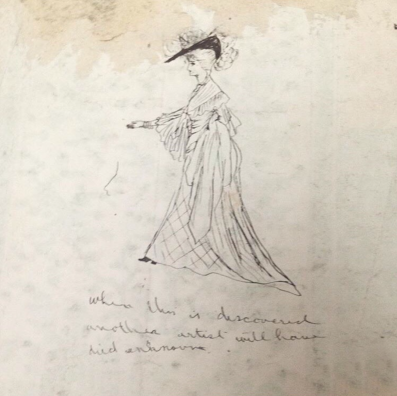

Paisley, Scotland, as the name suggests, was one of the epicenters of creation for these shawls. While by no means the only manufacturer (or the only name for the cone shape design), the town had been a textile-based industry and the popularity of these pieces ushered in for artists, a fervor of design possibilities. While many of these designers remain unnamed, the legacy of the art they produced lives on.

It is my guess that both these pieces came into the collection as collector’s pieces. However, it is certainly possible, given the earlier design of 1961.804, that this was a piece belonging to Elizabeth as part of her wardrobe. There are numerous small clustered repairs around the length edge trim, which fits with it being worn in one popular style for sure. Shawl 1961.85 shows fewer repairs and could have been used as a throw or as an accent at the end of a bed. It is a fine example of popular style, no matter the initial purpose it was purchased for.

- Dr Dan Coughlin, Visual Art Curator and Weaver at Paisley Museum and Art Galleries. Personal Notes, January 2016.

- Caroline, Karpinski. “Kashmir to Paisley”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Vol. 22, No. 3, Nov. 1963. https://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3258212.pdf.bannered.pdf

- Rossbach, Ed. The Art of Paisley. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co: 1980.

- Reilly, Valerie. The Paisley Pattern The Official Illustrated History. Richard Drew, Glasgow: 1987.

- Andrews, Meg. “Beyond the Fringe: Shawls of Paisley Design”. Victoriana Magazine. http://www.victoriana.com/Shawls/paisley-shawl.html

- Levi-Strauss, Monique. The French Shawls. Dryad Press Limited: 1987

- Ames, Frank. The Kashmir Shawl and Its Indo-french Influence. Antique Collectors’ Club: 2004.

Further information:

DRESSED: The History of Fashion. April Calahan & Cassidy Zachary. Podcast. “Cashmere with a “K”: The Controversial History of a Shawl”. May 15, 2018.

A Jacquard loom in action. Demonstrated by Dr Dan Coughlin: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OlJns3fPItE

You must be logged in to post a comment.