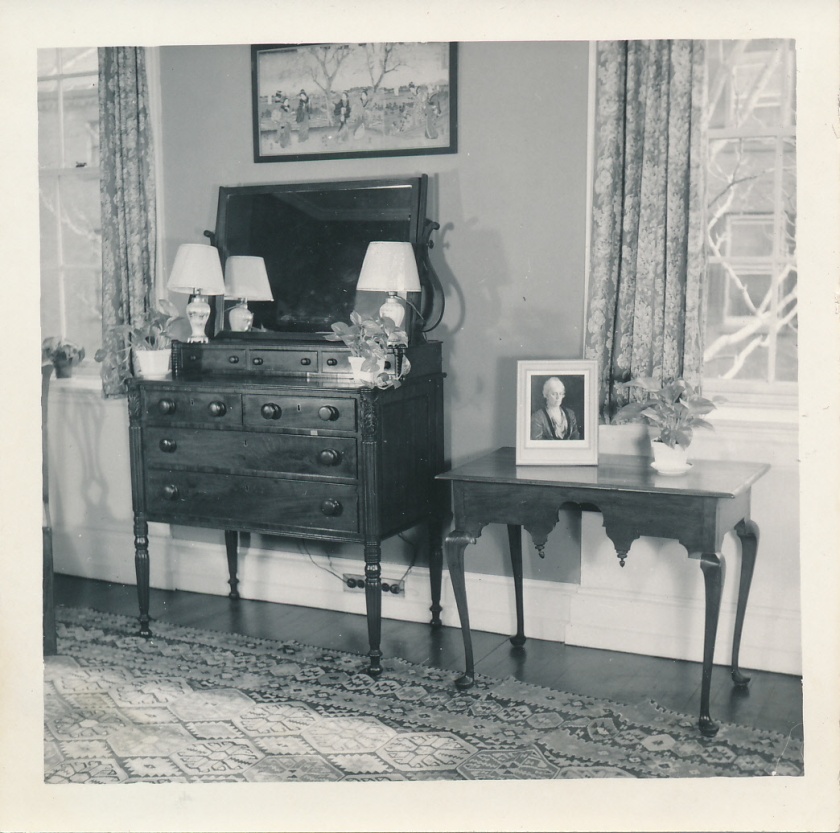

While there is very little blank space on Rose’s Mount Vernon Street bedroom walls, there are three Japanese woodblock prints that stand out. Two of the prints are by Andō Hiroshige (1797-1858). The first is entitled “Cherry Blossoms on the Bank of the Sumida River” and pictures the hundreds of cherry blossom trees on the Sumida River where many festivals are held. The second is “Scene of Yedo” which is believed to picture Edo (now modern Tokyo) and also celebrates the cherry blossoms, which only bloom for two weeks a year. The other print is by Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825) and is entitled “Mare Sankura Portrait” and features the 18th century Kabuki actor Mare Sankura.

The three woodblock (nishiki-e) prints were made during the Edo period, which is characterized by peace and prosperity. There was a strict hierarchical class structure during this time. Samurais protected the emperor and Zen Buddhism and Confucianism emerged as powerful societal influences.[1] Japanese citizens became more intellectually engaged and the arts flourished. Making one woodblock print required work from many different people. Each print required a designer, engraver, printer, and publisher.[2] The prints are done in the ukiyo-e style, which translated from Japanese means “pictures of the floating world” and is a Buddhist concept that represents the transience of life.[3] Woodblock printing was popular because once the woodblock was engraved the prints could be mass-produced. It makes sense that this would be true since the ukiyo-e movement was characterized by its widespread appeal because it made portraits of the famous more accessible to many classes.[4]

Toyokuni was from Edo and helped to popularize the ukiyo-e style. He specialized in prints of theater actors and women, just like the one we see here in Rose’s room featuring a Kabuki actor. Here, a theater actor, Mare Sankura, bears two scabbards with two swords protruding from his kimono sash, or obi.

Toyokuni’s vivid and dramatic work really represented the foundations of the style, as he was an earlier member of the movement.[5] In fact, Hiroshige wished to be his student but as not accepted into his school. Instead, Hiroshige, also born in Edo, worked with Utagawa Toyohiro who took his work in a different direction. Instead of bringing Japan’s beautiful women and actors to the masses, Hiroshige wanted to cover Japan’s beauty and show everyday life through landscapes.[6] Hiroshige reached a higher level of popularity than Toyokuni did and his works inspired the likes of Vincent Van Gogh and Claude Monet.[7] He represented the back half of the ukiyo-e movement, which met its demise with the modernization of Japan.[8]

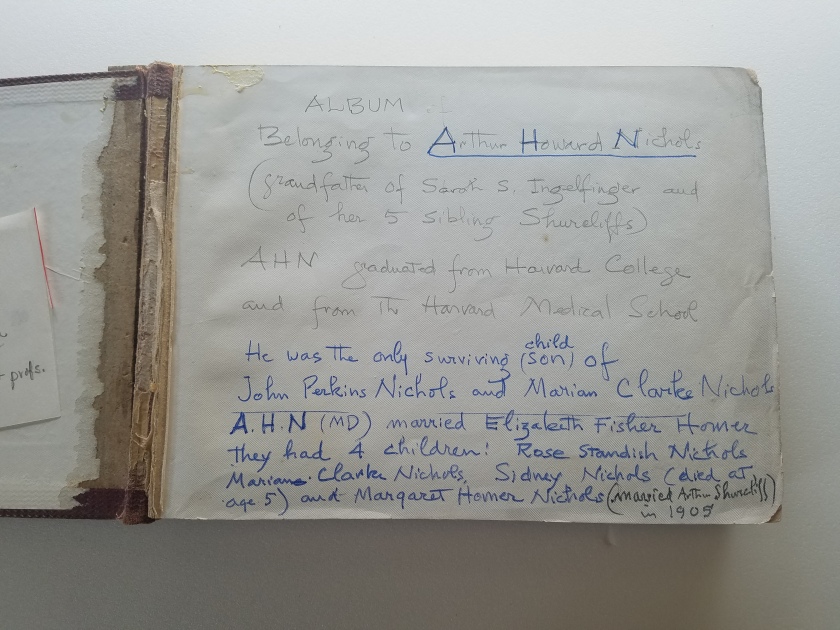

Rose acquired these prints from a Japanese friend, R. Kita, in 1934 although the current display of the three prints dates to 1947. In Rose’s records only the two Hiroshige prints are specified and there is a third unnamed print. A previous museum caretaker at the Nichols House Museum, William Pear, did some investigation into the framing of these three prints and found that the framer, Carl E. Nelson, framed all three of these prints and was out of business by 1947. This is the year we have records of the current arrangement of the prints and so it is likely that the third unnamed print in Rose’s records is the Toyokuni print since all three prints were framed by Nelson.

While Rose’s set of Japanese wood block prints is limited to three, there are more prints to be seen in Boston this month. The MFA’s exhibition of ukiyo-e prints from the Edo Period entitled “Showdown! Kuniyoshi vs. Kunisada” has just opened.

By Olivia Reed, Summer 2017 Administrative Intern

[1] “The Edo Period in Japanese History.” Victoria and Albert Museum. 2016. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/the-edo-period-in-japanese-history/.

[2] Department of Asian Art. “Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2003. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ukiy/hd_ukiy.htm.

[3] Department of Asian Art. “Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2004. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/plea/hd_plea.htm.

[4] Department of Asian Art. “Art of the Pleasure Quarters…”

[5] “Utagawa Toyokuni.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Nov 01, 2007. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Utagawa-Toyokuni.

6] “Hiroshige.” Ronin Gallery. Accessed August 15, 2017. http://www.roningallery.com/artists/hiroshige?p=2.

[7] William H. Pear II, Museum Inventory Memo, Nichols House Museum.

[8] Department of Asian Art. “Art of the Pleasure Quarters…”

You must be logged in to post a comment.