By Elizabeth Weisblatt, Dress and Textile Historian and Visitor Services Representative at the Nichols House Museum

For this Object Spotlight, we’ll be looking more in-depth at one of the samplers housed in Museum’s collection storage.

Samplers have a very long history, with the earliest known sampler dating to the second century BCE and used as a sketchbook of sorts, with stitched patterns in random order. With time the layout of such pieces became more organized with clear pattern endings.

As pre-printed patterns were few, a needleworker would create a sample of a pattern when they saw a new pattern, creating a collection of sample patterns. Samplers were known to be used by stitchers in Europe as early as the beginning of the 16th century, although none that early have survived. What has survived from that period are the inventories and wills of many European royals and noble families, many of which include a number of samples, including the Spanish royal family. In the 1509 inventory of Queen Joanna (Juana I, 1479-1555) of Castile, there are 50 samplers (dechados) listed, described as stitchery and drawn work, some of which were in silk and gold thread [1].

By the 18th century, sampler making had become an important part of girls’ education in boarding and institutional schools. Components of these pieces began to include the alphabet and numbers, often accompanied by various crowns, coronets, or other patterns all used in decorating and marking household linens. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, schools or academies for well-to-do young women were flourishing. There, they created more elaborate pieces with decorative motifs such as verses, flowers, houses, religious, pastoral, and/or mourning scenes being created [2].

Traditional embroidered motifs were now rearranged into decorative borders framing lengthy inscriptions or verses of an “improving” nature and small pictorial scenes. These new samplers were more useful as a record of accomplishment to be hung on the wall than as a practical stitchers guide.

In addition to patterns, samplers also can give a connection to the country where they were created based on shape, color, and design [3]. While British, American, and Mexican samplers often have the alphabet or poem incorporated into a larger design, Spanish samplers rarely do. However, as design books became published and distributed, the use of patterns is often not overly helpful when looking into where the sampler was created. Printed pattern books, although common throughout most of Europe after the 16th century, remained rare in Spain and Spanish territories, where samplers continued to serve as design inventories [4].

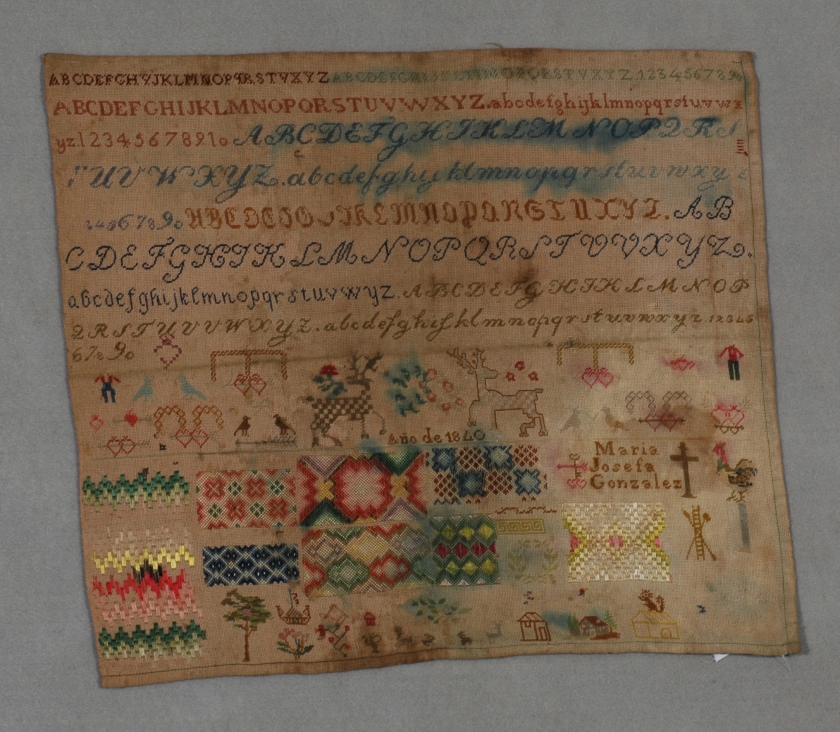

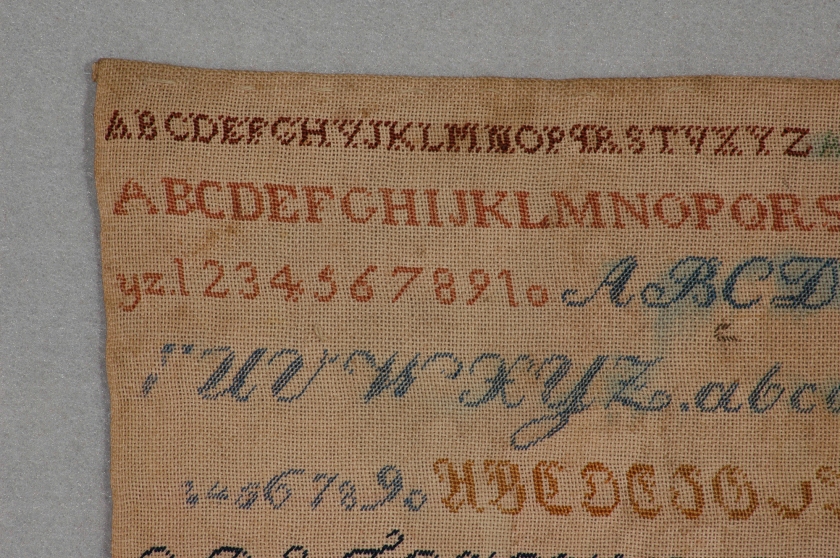

The many samplers in the Nichols House Museum collection vary in date, where they were created, and degree of completion. One example illustrating a wide range of motifs was made by a Maria Josefa Gonzalez in 1840, likely produced in Mexico (1961.742a-b). Made on linen with silk thread, her sampler has not one, not two, but eleven different stylized alphabets and numbers, from simple lowercase block letters to flowing capital script letters on the top half of the sampler.

The lower half contains multiple different repetitive patterns that could be repeated when embroidering larger pieces in the future, as well as deer, birds, trees, and small buildings. The repetition of the sacred heart motif as well as the large cross next to Maria’s name suggests that this piece was created in Mexico or South America, as religious motifs where more prevalent there than in Spain [5].

Maria’s sampler utilizes two stitches: a tent stitch, which consists of a single slanted or diagonal stitch across one canvas intersection, and a satin stitch, which is a series of flat stitches that are used to completely cover a section, often giving a shiny effect. These stitches would be useful as a basis of female education for their utility both in ornamentation and in designing and repairing garments.

Rose Standish Nichols was a textile and embroidery artist herself and she collected antique samplers with special interest and care. Learn more about her collection of textiles as well as her own needlework and embroidery under the Tapestries and Textiles section of our website.

[1] Luis González García, Juan. “Charles V and the Habsburgs’ Inventories. Changing Patrimony as Dynastic Cult in Early Modern Europe,” in: RIHA Journal 0012 (11 November 2010). http://www.riha-journal.org/articles/2010/gonzalez-garcia-charles-v-and-the-habsburgs-inventories.

[2] 1. Beck, Thomasina. The Embroiderer’s Story: Needlework from the Renaissance to the Present Day. 1999. David & Charles.

[3] Huish, Marcus Bourne. Samplers & tapestry embroideries. 1913. London, New York [etc.] Longmans, Green and co. https://archive.org/details/samplerstapestry00huisrich/page/12

[4] V&A · Mexican embroidery, Victoria and Albert Museum. June 2018. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/mexican-embroidery

[5] Beusen, Denise D. “Patterns From The Past: Mexican Samplers of the 19th Century” Needle Pointers, July 2003. http://www.beusen.net/Needlework/19thCenturyMexicanSamplers.pdf

You must be logged in to post a comment.