Rose Standish Nichols published her third book, Italian Pleasure Gardens, in 1931. In preparation for this book, as well as at least twelve magazine articles that she wrote about Italian garden design and tradition, she took many trips abroad. Evidence of her travels through Italy can be found in letters, postcards, and dozens of objects in her collection of fine and decorative art. Her collection of Italian objects includes paintings, marquetry furniture, and even a reliquary. However, many of the objects that she collected from Italy are ceramic.

Included in her collection of Italian pottery are three majolica busts, including a copy of Andrea della Robbia’s “Bust of a Boy.”

Tin-glazed pottery, or majolica has a uniquely opaque and glossy finish, which allowed artists to create a pure white ground for brightly colored patterns that would be dulled on the natural surface of clay.[1] Luca della Robbia (1399/1400-1482) [2] was one of the Italian ceramicists who is credited with popularizing majolica during the Renaissance in his home city of Florence. While the technique of created tin-glazed ceramics was known before his time, Luca della Robbia’s elevated enameled terracotta to a fine art material, as he was considered a “sculptor first, and a potter afterwards.”[3] Luca della Robbia instructed his nephew, Andrea della Robbia, in the techniques he used to create his signature brilliant white and blue glazes and the subsequent della Robbia family workshop operated for close to a century. [4]

In the mid to late-nineteenth century, a revival of Renaissance styles in architecture and decorative arts swept through America and Europe,[5] prompting ceramic studios to begin making majolica pottery once again, including Cantagalli.

Ulisse Cantagalli inherited a Florentine pottery studio from his father in 1878. Cantagalli took over his family’s business that had focused on functional earthenware, and began creating terracotta reproductions of Italian masterworks. These reproductions were moderately priced, making them more readily available.[6] Cantagalli’s maker’s mark is a gestural drawing of a rooster.[7] This inscription is found on Rose Standish Nichols’ copy of della Robbia’s majolica bust.

In Rose Standish Nichols’ collection are two other majolica busts, possibly from Cantagalli’s workshop, including a reproduction of a Verrochio sculpture depicting Piero de Medici.

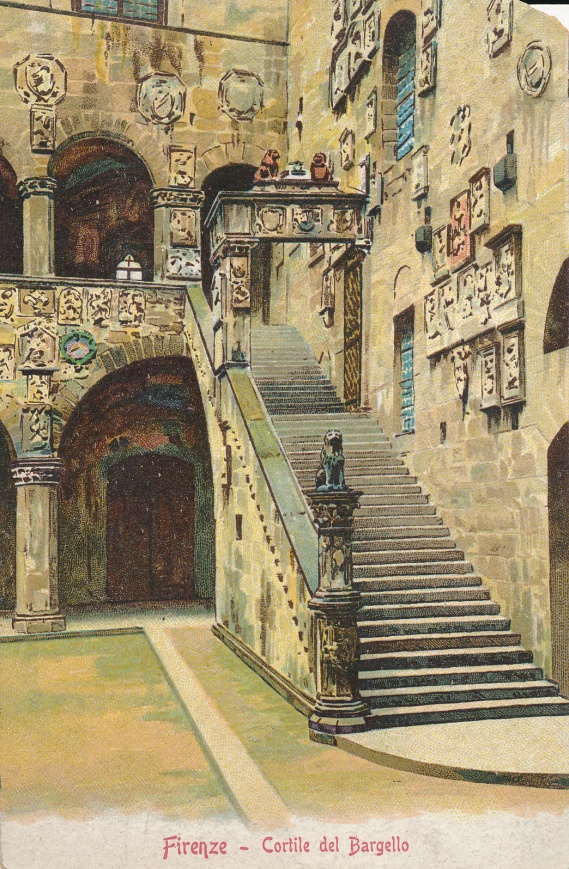

As Rose Standish Nichols was collecting these reproduction ceramics, she was also becoming familiar with the originals. Della Robbia’s Bust of a Boy, as well as Verrochio’s likeness of Piero de Medici, are both part of the collection of the Museo Nazionale Bargello in Florence. In her 1931 book, Italian Pleasure Gardens, she describes works now found in the Bargello as they were displayed in their original location at the Palazzo Medici in Florence.

To the fondness for art of Piero, Cosimo’s son and successor, and to the encouragement of his wife, Lucrezia Tornabuoni, the palace owed many of the famous works of art contained there…Of Piero’s own careworn appearance, however, we can obtain a more accurate idea from his bust by Mino da Fiesole now in the Bargello.

In the days of Lorenzo the Magnificent, the palace was a museum, overflowing with the paintings and sculptures he had added to the previous collections. Verrochio’s little David, now in the Bargello, stood in the centre of the court, while the Boy with the Dolphin above a fountain-basin, now transferred to the Palazzo Vecchio, seems to have ornamented the garden at the rear, and Judith with the head of Holofernes also stood there.[8]

Rose Standish Nichols’ knowledge of Italian Renaissance artists and patrons clearly impacted her own collecting practice as well as her scholarship. The three majolica busts found on shelves and mantles throughout her home signify her interest in the influential collectors of the Renaissance and are reminiscent of her many travels through Italy.

[1]Solon, L. M. A History and Description of Italian Majolica. London: Cassell and, Limited, 1907. 76. Print.

[2]“Della Robbia.” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. N.p., 08 May 2017. Web. 12 May 2017.

[3]Elliott, Charles Wyllys. “Italian Majolica.” The Art Journal (1875-1887) 3 (1877): 244. Web. 16 May 2017.

[4]”Della Robbia.” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. N.p., 08 May 2017. Web. 12 May 2017.

[5] Victoria and Albert Museum, “Style Guide: Classical and Renaissance Revival.” Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 31 Jan. 2013. Web. 12 May 2017.

[6] Solon, L. M. A History and Description of Italian Majolica. London: Cassell and, Limited, 1907. 53-54. Print.

[7] Cushion, J. P., and W. B. Honey. Handbook of Pottery and Porcelain Marks. London: Faber and Faber, 1980. 171. Print.

[8] Nichols, Rose Standish. Italian Pleasure Gardens. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1931. 67. Print.

By Emma Welty, Head of Collections and Education.

You must be logged in to post a comment.