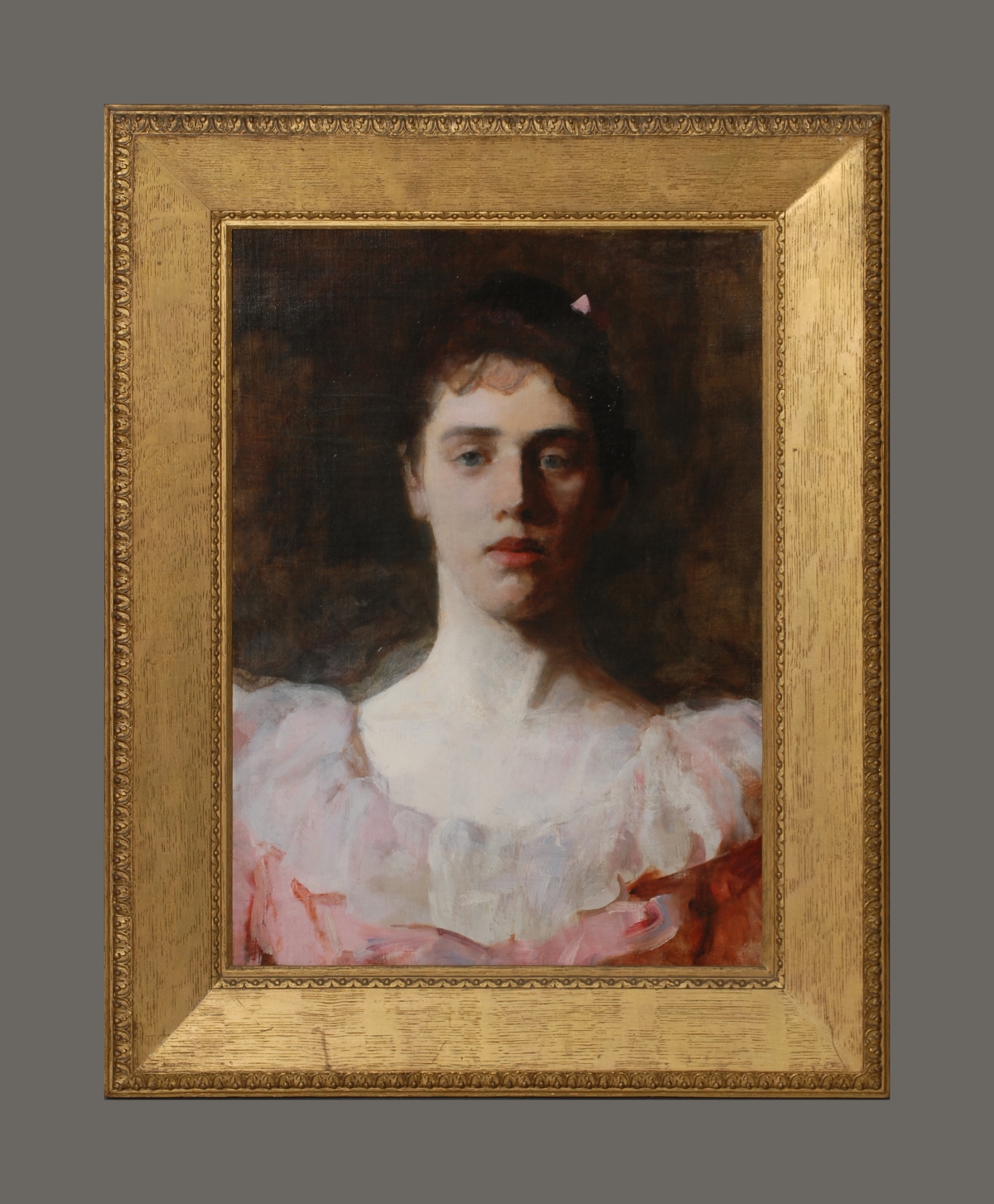

Today marks Rose Standish Nichols’ 145th birthday. To celebrate this day we are looking back at a likeness of Rose created shortly after her eighteenth birthday: an oil painting showing Rose with a powerful gaze and a pink dress. This painting represents Rose during a time of her life when most women her age were expected to focus on attracting a male suitor. Whether or not Rose was interested in finding a husband is open for interpretation. A few letters suggest an interest in romance yet her posture and tone in this painting of her as a young adult illustrates a fiercely independent and assertive woman.

There are some very attractive people at this hotel. Next [to] me at [a] table is one of the handsomest and swellest looking men I have ever seen…How I wish you could see this kind of perfection at dinner in a dress-suit with his moustache waxed to an inimitable points…Now I suppose you can’t help wondering if I am not deeply in love for once in my life.

Rose to Marian, 1896.

Rose lived 88 years independently but was rarely alone. She had a large network of friends and colleagues from all walks of life, both at home and internationally. One of her friends, Margarita “Daisy” Pumpelly, was the artist that painted her portrait in 1890. Daisy was born in 1873, one year after Rose, and died in 1959, one year before Rose. Their families, both from Boston, vacationed in Cornish and Dublin, active artist communities in New Hampshire. Rose and Daisy were both artistically gifted, apprenticing with local artists in New Hampshire and continuing their studies in Europe. [1] Despite all the parallels in the lives of the two women, one thing set them apart: Daisy was married.

Daisy Pumpelly married Henry “Harry” Lloyd Smyth in November 1894, when she was 21 years old. Despite her marriage to Harry, a geologist at Harvard University, and their four children, Daisy maintained an independent lifestyle. [2] In September of 1894, two months before Daisy and Harry’s wedding, Daisy’s sister wrote to Rose’s sister, Marian about Daisy’s travels in Paris:

“Daisy writes glowing accounts of Paris they had several adventures on the way. I should think that she would be excited at the thought of seeing Harry so soon, but to all appearances she does not show it.”

Elise Pumpelly to Marian, September 6, 1894.

Throughout Daisy and Harry’s marriage, they often traveled independently. In the Nichols family’s correspondence, mentions of Daisy and Harry in the same place are infrequent. She even traveled out West in 1920 with her father and two siblings, while Harry remained in New England. [3]

The link between Rose Nichols and Daisy Pumpelly Smyth is deeper than friend to friend or artist to sitter. Rose and Daisy both represent independent and artistic women at the turn of the twentieth century, committed to their careers and artistic practices despite societal expectations. On Rose’s 145th birthday we celebrate a portrait, connecting the lives of two female friends through art and social progress.

[1] Quirk, Lisa. “Margarita Pumpelly Smyth.” A Circle of Friends: Art Colonies of Cornish and Dublin. Durham: University Art Galleries, University of New Hampshire, 1985. 117.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid

[4] Pumpelly, Raphael. My Reminiscences. New York: Henry Holt, 1918. 779. Print.

[5] Thompson, Juliet, and Marzieh Gail. “At 48th West Tenth.” The Diary of Juliet Thompson. Los Angeles: KalimaÌt, 1983. X.

[6] Parsons, Agnes. Abdu’l-Bahá in America, Agnes Parsons’ Diary, April 11 1912 – November 11, 1912. Los Angeles: Kalimát, 1996. 154.

By Emma Welty, Head of Collections and Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.