Chair

Carving: Rose Standish Nichols

Chair frame: Irving & Casson-A.H. Davenport Co.

Made: Boston, Massachusetts, 1910-1940

Materials: Oak, cane

To see this object in the Nichols House Museum online collection, search for 1961.100.1 here: http://nicholshouse.pastperfect-online.com/36637cgi/mweb.exe?request=ks

Rose, Marian, and Margaret, the three Nichols family daughters, represent the meeting of Beacon Hill tradition and the emerging New Woman of the twentieth century.[1] They were raised in a traditional nineteenth-century upper class Boston home, but Dr. and Mrs. Nichols educated their daughters at a progressive school.

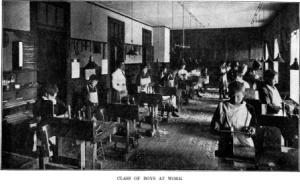

After moving to the house at 55 Mount Vernon Street, Marian and Margaret attended a private school founded by Mrs. Pauline Agassiz Shaw.[2] Boston private schools at this time were typically all boys or all girls. While girls fortunate enough to enroll in city, rather than rural, schools were taught a curriculum similar to boys’, the coursework was almost exclusively academic.[3] In contrast, at the innovative Mrs. Shaw’s School boys and girls were educated together, and the students learned to work with their hands in addition to customary academic lessons. This included woodworking and book binding. We know that Rose and Margaret both studied woodworking, and both pursued this into adulthood.[4]

Mrs. Shaw’s School taught the educational sloyd woodworking method to its students. Sloyd was a system of instructing children in woodworking that was founded on the principle of holistic education — employing the hands to better the mind.[5] The program’s creators believed that students would develop stronger character by learning values like self-reliance, patience, and an appreciation for hard work through learning carpentry.[6]

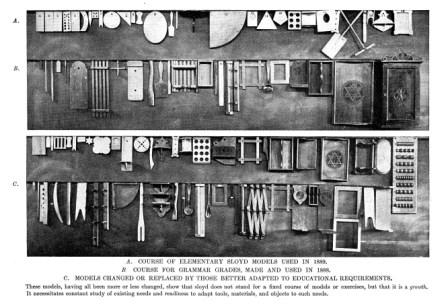

Otto Salomon, a nineteenth century Swedish educator, studied and adapted the ideas of a Finnish education reformer and brought them to his teachers’ school at Nääs in the 1870s, where he began to train teachers for educational sloyd.[7] The teaching system entails a process of increasingly complex model making, where students learn new skills and the use of new tools with each model, or project.

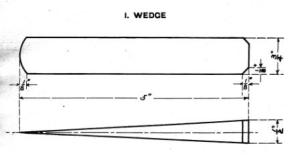

One of Salomon’s trainee teachers, Gustaf Larsson, brought sloyd to Boston in the late 1800s. Mrs. Shaw’s School hired Larsson in 1889 to teach its students sloyd, and named him the director of the program in 1891.[8] The Nichols family moved to 55 Mount Vernon Street in 1885, so it was around this time the girls attended the school and learned woodworking. In her memoirs, Margaret recalls that of her courses, sloyd was “[t]he most fun of all.”[9] She wrote of making several models like a window wedge, flower stick, and sleeve board, all of which can be found in Larsson’s textbook, Sloyd for the Three Upper Grammar Grades.[10]

Later in life, Margaret opened a carpentry shop called Pegleggers in her home. She worked with two other women making reproduction antique furniture using accurate period tools.[11] Margaret also taught woodworking to immigrant children living in settlement houses so they could support themselves with a trade.[12]

Rose enjoyed woodwork as more of a hobby. She used her skill to ornament pieces that would decorate her home. Four chairs displayed in the museum’s library are her work and date from the early twentieth century. Rose was influenced by the Colonial Revival decorative style of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Colonial Revival looked back to older, “traditional” American forms and coincided with the Arts and Crafts Movement that valued handmade pieces rather than manufactured objects. For these chairs, Rose combined the American desire to look to the past with English inspiration. Rose would have seen many examples of English traditional designs while researching the formal gardens of England’s great houses for her first book. Rose completed the carving on the chair pictured here, modeled on an original seventeenth-century English chair on view in the museum’s dining room. The original beech chair is from the late 1600s but decorated in the Jacobean style of the earlier decades of that century.

Rose’s work on the oak chairs closely follows the English Jacobean model’s scrolls, daisies, putti (cherub-like figures), and expertly turned stiles, legs, and stretchers.

Rose Nichols and her sisters were women of many talents. As “New Women,” they pursued physical, intellectual, and career interests that had been closed to most women who came before them. Some of these pursuits left physical objects, like Rose’s carved chairs, but their important social, political, and civic work had more intangible effects. To learn more about the Nichols daughters’ activism, please visit us at the museum!

By Collins Warren, Summer 2015 Intern

Collins is a master’s student in history and museum studies at Tufts University. During her internship with the museum, she is assisting with collections management and research, as well as giving tours. One of her favorite pieces in the collection is the caricature sketch of Rose drawn by her uncle, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, which is displayed on the desk in Rose’s bedroom.

[1] To learn more about the concept of the “New Woman” in the American Progressive Era, visit the National Women’s History Museum’s online exhibit: https://www.nwhm.org/online-exhibits/progressiveera/statuswomenprogressive.html.

[2] We know from Arthur Nichols’s family expense records that Rose attended Miss Folsom’s finishing school in 1889, and from letters and memoirs that Marian and Margaret both attended Mrs. Shaw’s School. While it is likely that Rose also went to the Shaw School for a time after moving to 55 Mount Vernon Street because she was just one year older than Marian, we have no definitive documentation of her attendance.

[3] Stephanie Kermes, “‘To make them fit wives for well educated men’? 19th-Century Education of Boston Girls,” Boston Historical Society, http://www.bostonhistory.org/pdf/Kermes%20article_final.pdf.

[4] Margaret Homer Shurcliff, Lively Days: Some Memoirs (Boston: The Board of Governors, Nichols House Museum, 2011), 7-8, 43.

[5] Doug Stowe, “Educational Sloyd: The Early Roots of Manual Training,” Woodwork, August 2004, 67, http://dougstowe.com/educator_resources/w88sloyd.pdf; David J. Whittaker, The Impact and Legacy of Educational Sloyd: Head and Hands in Harness, in collaboration with Gisli Thorsteinsson, Brynjar Olafsson, Aki Rasinen, and Esa-Matti Järvinen (New York: Routledge, 2014), 25.

[6] Whittaker, Impact and Legacy, 34.

[7] Whittaker, Impact and Legacy, 15, 26, 32-33; Stowe, “Educational Sloyd,” 67.

[8] Stowe, “Educational Sloyd,” 68.

[9] Shurcliff, Lively Days, 8.

[10] Ibid.; Gustaf Larsson, Sloyd for the Three Upper Grammar Grades, teachers’ ed. (Boston: George H. Ellis Co., 1907). http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89097455919;view=1up;seq=73

[11] “Pegleggers” business card, courtesy of the Shurcliff Family, Nichols House Museum.

[12] Shurcliff, Lively Days, 44-45.

You must be logged in to post a comment.